Seeing feels effortless, almost passive. Light floods in, an image appears in our mind, and we perceive the world. But this seamless experience masks an incredibly complex and active process orchestrated by our brains. Vision isn’t just about the eyes acting like cameras; it’s about the brain interpreting, constructing, and sometimes even guessing, based on the raw data received. Artists, perhaps more than anyone, intuitively understand the quirks and shortcuts of our visual system. They are masters at manipulating these neurological processes to guide our gaze, evoke emotions, and even make us see things that aren’t strictly there.

The Journey from Light to Perception

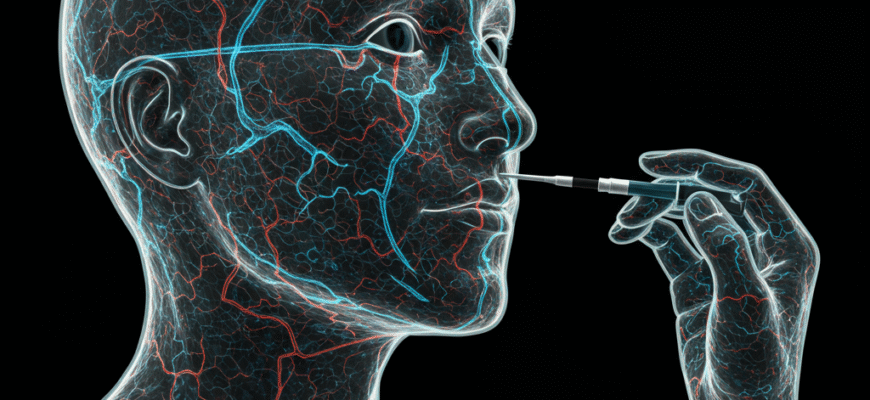

The process begins when light reflects off an object and enters the eye, focused by the lens onto the retina. The retina isn’t just a passive screen; it’s a piece of brain tissue containing photoreceptor cells (rods and cones) that convert light energy into electrical signals. Cones handle color and detail in bright light, while rods manage vision in dim light. These initial signals are already processed by other retinal neurons before being sent down the optic nerve.

From the optic nerve, signals travel to the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus (LGN) in the thalamus, a sort of relay station, before reaching the primary visual cortex (V1) at the back of the brain. But V1 is just the beginning. From here, information splits into different pathways, broadly characterized as the “what” pathway (ventral stream, identifying objects) and the “where/how” pathway (dorsal stream, processing location, movement, and guiding actions). Each stage involves intricate processing, feature detection (like edges, orientations, colors), and integration.

Understanding the Visual Pathway: The journey of visual information is far from a simple snapshot transfer. It involves multiple stages of processing, starting in the retina itself, moving through relay stations like the LGN, and fanning out into specialized cortical areas. Each step actively interprets and transforms the incoming signals.

Crucially, this isn’t a one-way street. There’s significant feedback from higher brain areas back to earlier ones. This means our expectations, attention, and past experiences actively shape what we perceive even at relatively early stages. Our brain constantly makes predictions and compares them to incoming data, constructing our visual reality moment by moment.

Artists as Intuitive Neuroscientists

Long before neuroscience could map these pathways, artists were experimenting with perception. They discovered techniques that reliably produced certain effects in the viewer, essentially hacking the visual system. They didn’t need fMRI scans to know that certain color combinations vibrate, that lines could create depth, or that shadows define form. They learned through practice, observation, and a deep understanding of how humans *see*.

Manipulating Color: Beyond the Spectrum

Color perception is one of the most fascinating and exploitable areas. Our brain doesn’t just register wavelengths; it interprets them in context.

Color Constancy: Our brain tries to perceive the color of an object as constant, even under vastly different lighting conditions (think of a white shirt looking white both indoors under yellowish light and outdoors under blueish daylight). Artists can play with this. They might exaggerate the subtle color shifts caused by light to create mood, or deliberately break constancy to make a scene feel unnatural or surreal.

Simultaneous Contrast: How we perceive a color is heavily influenced by the colors surrounding it. A grey patch will look lighter against a black background and darker against a white one. It can even take on a complementary hue – grey might look slightly reddish when surrounded by green. Josef Albers dedicated much of his career to exploring these interactions in his “Homage to the Square” series, demonstrating how the same color could appear dramatically different depending on its neighbors. Impressionists and Post-Impressionists like Monet and Van Gogh used this instinctively, placing complementary colors side-by-side (blue and orange, yellow and violet) to make them appear more vibrant and intense.

Emotional Resonance: Artists have long understood the psychological impact of color – reds and yellows often perceived as warm, energetic, or even aggressive, while blues and greens are seen as cool, calm, or receding. This isn’t purely cultural; there might be underlying neurological links related to evolutionary associations (e.g., fire and warmth, water/foliage and calm). Artists use these associations deliberately to set the mood of a piece.

Creating a convincing illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface is a cornerstone of representational art, relying heavily on manipulating perceptual cues the brain uses to judge depth and form.

Linear Perspective: Perfected during the Renaissance, this system uses converging lines (orthogonals) that meet at vanishing points on the horizon line to mimic how parallel lines appear to recede in the distance. This directly exploits how our brain interprets geometric patterns to understand spatial layout.

Atmospheric Perspective: Leonardo da Vinci was a master observer of this effect. Objects further away appear less sharp, lower in contrast, and often slightly bluer or hazier due to particles in the atmosphere scattering light. Artists replicate this to enhance the sense of distance.

Occlusion and Overlap: One of the simplest and most powerful depth cues. When one object partially blocks the view of another, our brain instantly assumes the blocking object is closer.

Light and Shadow (Chiaroscuro): Our brain uses shading to understand the shape and volume of objects. The way light falls across a surface, creating highlights and shadows, provides crucial information about its form. Artists like Caravaggio and Rembrandt used dramatic contrasts between light and dark (chiaroscuro) not just for mood, but to sculpt figures and make them appear powerfully three-dimensional.

Exploiting the Brain’s Assumptions: Illusions and Ambiguity

Our visual system is built for efficiency. It makes assumptions and uses shortcuts to interpret the world quickly. Artists can target these mechanisms to create fascinating and sometimes unsettling effects.

Op Art: Artists like Bridget Riley and Victor Vasarely created works that directly stimulate neurons in the visual cortex in specific ways, often using repeating patterns, high contrast, and precise geometry. This can create illusions of movement, shimmering, or vibration where none exists, essentially overloading or tricking the brain’s motion and edge detectors.

Ambiguous Figures: Think of the classic Rubin’s Vase (which can be seen as a vase or two faces) or the works of M.C. Escher. These exploit the brain’s struggle to settle on a single interpretation when presented with conflicting cues, particularly regarding figure-ground segregation (determining what is the object and what is the background). The brain flips between possible interpretations.

Gestalt Principles: The Gestalt school of psychology identified principles describing how our brain tends to group visual elements into unified wholes. Artists use these intuitively:

- Proximity: Objects close together are perceived as a group.

- Similarity: Objects that look similar (in shape, color, size) are seen as belonging together.

- Closure: Our brain tends to complete incomplete shapes, filling in the gaps. Think of how a circle drawn with dashed lines is still perceived as a circle.

- Continuity: We prefer to see smooth, continuous lines or patterns rather than abrupt changes. Our eye will follow a line or curve naturally.

- Figure-Ground: Our tendency to separate a main object (figure) from its surroundings (ground).

Artists use these principles to organize their compositions, create visual pathways, and imbue elements with relationships and meaning.

Guiding the Eye: Attention and Saliency

Where do you look first in a painting? It’s rarely random. Artists carefully orchestrate the viewing experience, using visual cues to draw attention to specific areas – the focal point. They manipulate ‘saliency’, the quality that makes an element stand out.

Contrast: Areas of high contrast (light against dark, bright color against muted tones, sharp focus against blur) naturally attract the eye. Our visual system is wired to notice differences.

Lines and Direction: Actual or implied lines (like a pointing finger, a gaze direction, or the sweep of a landscape) can direct the viewer’s gaze through the artwork.

Human Figures and Faces: We are socially attuned creatures. Faces and human forms are powerful magnets for attention in art.

Isolation: An object placed alone in a relatively empty space will naturally draw focus.

By controlling these elements, artists don’t just present an image; they choreograph our perceptual journey through it.

The Active Viewer: Remember that perception is not passive reception. Your brain actively constructs your visual reality using built-in rules, learned associations, and contextual cues. Artists leverage this active construction, playing with the very mechanisms you use to make sense of the visual world every moment.

Art as a Window into the Brain

Studying how artists manipulate perception offers a fascinating window into the workings of our own visual system. It reveals that seeing is not just about detecting light, but about constructing meaning, interpreting ambiguity, and experiencing the world through a brain that is constantly predicting, organizing, and filling in the blanks. The techniques developed by artists over centuries serve as powerful demonstrations of the principles neuroscientists are now uncovering in the lab. Appreciating art, therefore, becomes not just an aesthetic experience, but an exploration of the intricate and wonderful ways our brains create our sense of sight.